Macroeconomics in Covid and after: the Perfect Storm for Cryptocurrencies

Key Takeaways:

- The global debt explosion raises longer-term inflation risk, and Bitcoin is increasingly seen as a credible hedge against this

- Negative yields move out along the credit and duration curves, enhancing the allure of cryptocurrencies

- Central bank digital currencies start to appear, and may potentially have a positive interaction with private cryptocurrency ecosystems

Introduction

The Covid crisis has caused great macro-economic upheaval: soaring budget deficits and government debt, accompanied by new rounds of monetary easing on top of already ultra-easy stances. Alongside, there have been major structural changes: a surge in online shopping and supporting infrastructure, ranging from delivery logistics to body-scanning apps for clothes purchases; declining use of cash and a new round of pressure on many banks; a new phase of the tech cold war, as China races to develop its own world-beating chips; and an extraordinary change in travel and work patterns, evidenced in the collapse in flights, the boom in video calls, and the pop-up of cycle lanes across the world’s cities.

Cryptocurrencies find themselves at the heart of this upheaval, reflecting the features hard-wired into them by their creators. Bitcoin’s pre-determined path towards a future fixed supply stands in stark contrast to the unlimited potential to expand conventional currencies; newer cryptocurrencies offer functionality and earning power undreamt of in old-fashioned money; and central bank digital currencies, a year ago of little more than theoretical interest, have quite suddenly started to become a reality, in a way that may yet make them the perfect complements, rather than competitors, to their private counterparts. 2021 starts with a ‘perfect storm’, in which these fundamental characteristics of cryptocurrencies interact with the macro and sectoral effects of Covid, to broaden the their appeal far beyond the early enthusiast base, out to a broader and growing range of private and institutional investors.

This article is structured to consider in turn how each of the main macro and sectoral effects of Covid interacts with cryptocurrencies, at the end drawing the different areas together into a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts.

Macro – soaring debt, monetary ease, and what about inflation?

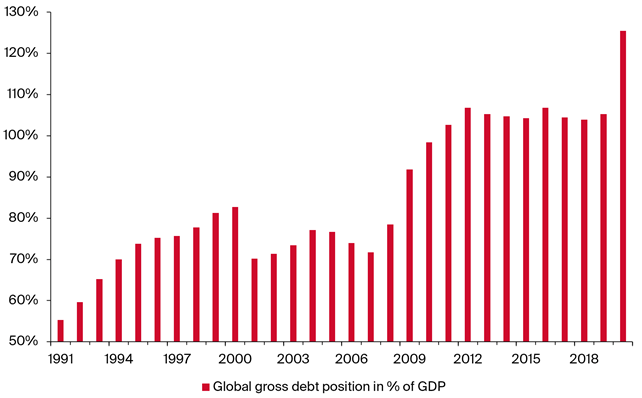

Developed-economy government debt at the end of 2020 is now estimated at 125% (IMF figures, gross basis, Illustration 1). That is based on figures published last October, when the full extent of the second wave of Covid had not become apparent, so the eventual figure is likely to be higher.

To give some historical context, the figure was 70% twelve years ago, just before the financial crisis, by the end of which it had lurched up to around 106%. After that, virtually no progress was made in reducing this debt burden, and so the effects of the Covid crisis and the financial crisis compound together.

The debt burden varies widely across countries, of course, with the US at 131% and Japan more than double that, while Germany is at 73% and Switzerland just below 50%. These figures would be lower, if government assets are netted off, and substantial portions of this debt is now held by central banks. Nevertheless, the big picture is clear: government debt was already very high before Covid, and it has soared as a result of the virus. The surge represents partly the lost tax revenue and increased benefits that operate automatically in a recession, and partly new measures to counter the economic weakness. There can be some improvement as the economy recovers, but it will be a grinding and slow process, and there are few signs of the political will to take the hard decisions needed to bring it down faster.

Yet, the risk that this extraordinary debt surge becomes dangerously unsustainable lies in the future; for now, it seems almost benign, and the reason is that the cost of debt service has barely risen or has even fallen, as a result of the parallel policy of ultra-easy money. Central banks around the world have abandoned the tentative steps towards tightening underway before the crisis and instead embarked on new rounds of easing. Zero or negative rates are now the global developed economy norm, and even many emerging countries have astonishingly low rates; quantitative easing has been expanded, not only in size but also in scope, with central banks buying assets that would have been unthinkable a few years ago, ranging from equities (Japan), to derestricted quantities of peripheral-economy bonds (Europe), and corporate and junk bonds (US).

These monetary measures have been highly successful in supporting asset prices, driving equity market multiples to high levels and compressing credit spreads. This has undoubtedly helped to minimise the depth of the Covid economic slump, but at the cost of over-valuing some assets in ways that inevitably distort resource allocation. For consumer good prices, it has probably helped to mitigate the risk of deflation, we don’t really know, but it clearly has not yet created an inflation.

And, this lack of inflation is just as well, for anything more than mild inflation could face central banks with an unpleasant dilemma: either they tighten policy (pushing rates up and ending asset purchases), which would trigger an economic downswing and raise the cost of servicing the debt mountain; or, they pretend the inflation isn’t happening, which works for a while until they lose credibility and bond yields then soar out of their control – unless they impose ‘financial repression’, with exchange controls and/or rules that force domestic investors to buy government bonds at low yields, effectively a confiscatory wealth tax.

So, how likely is the risk of such inflation? At present, not very likely, due to the slump in demand caused by Covid. And there is certainly a good chance that this slump will be followed by a gradual economic recovery, allowing central banks to start gently tightening policy over a period of several years, keeping inflation under control and avoiding the extreme scenarios just mentioned. But there are also darker scenarios. The “scarring” from Covid, with lower-skilled and older people driven out of the workforce and companies bankrupted, reduces economic capacity and may run the economy into the inflationary buffers much earlier than expected, unless countered by well-targeted re-training programmes. The move towards more nationalism in politics, and the new Cold War between the US and China, may encourage uncompetitive oligopolies that can push up prices easily – the recent antitrust action against the Google ad-monopoly appears to go against this, but has yet to be shown to have real teeth.

The bottom line is that we just don’t know how big is the risk of an inflation large enough to tip the debt mountain from benign to deadly – all we can say is that it’s a much bigger risk than it was before Covid.

Bitcoin in an era of debt and inflation

Bitcoin could have been designed as the perfect asset to protect investors from this debt-inflation spiral – and indeed, the need for such an asset does appear to have been one of its original inspirations. Because the supply of additional Bitcoin rises at a reducing rate and eventually stops, it is hard-wired to have a deflationary bias that no fiat currency could ever have. Provided there is ongoing demand to hold Bitcoin, as an investment and/or transactions asset, that has at least a loose positive correlation to overall nominal global GDP, then both real economic growth and inflation will, over time, create a tendency for its trend price to rise. And the risk of ‘financial repression’ mentioned above could add an extra impetus to this, for Bitcoin holdings, whether permitted or not permitted under dystopian future scenarios, could be difficult to detect.

Gold has traditionally been the asset held by investors concerned about runaway debt and inflation, but interestingly, it was the “dog that did not bark” in 2020, with its prices showing little strong uptrend in a year when cryptocurrency prices, though volatile, did trend upwards. One prosaic reason for that is that global jewellery demand has been weak, for a number of reasons, notably the decline in formal weddings in India and elsewhere; central bank demand has also been weak, for reasons that are not clear. But another key reason for the divergence between gold and cryptocurrency prices is that gold not only pays no interest, but actually costs money to hold. By contrast, cryptocurrency holdings can be used to generate substantial income, and we now turn to consider this.

Zero interest rates, the positive yield on cryptocurrency holdings, and the future of conventional banks

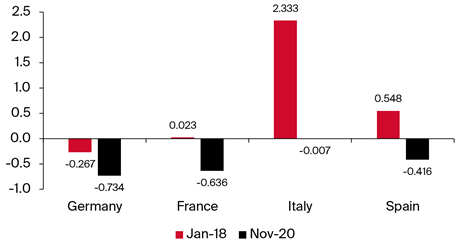

While near-zero or outright negative interest rates were already part of the ‘new normal’ when Covid struck, the monetary policy response to the virus has intensified their effect in a major way. In countries such as Switzerland, some banks have lowered the thresholds on which they charge depositors interest, but more profoundly, and globally, the action of the US Federal Reserve and others in buying investment grade and junk-rated bonds has compressed credit spreads. The result is that in many currencies, it is now barely possible to earn positive yields on fixed-income portfolios even by taking substantial credit and/or duration risk. Even emerging market debt portfolios now offer yields that would in the past have been associated with currencies such as the Euro or Swiss Franc (Illustration 2).

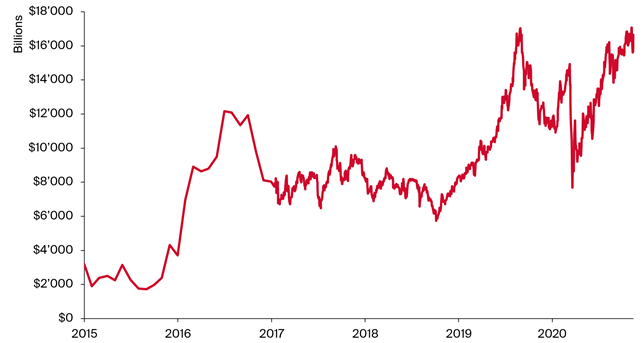

One stark illustration of the problem now faced by fixed income investors is that 26% of the market capitalisation of debt globally, over $17 trillion, now has a negative yield (Illustration 3).

This new lurch downwards in the ability to earn positive yields on mainstream portfolios has coincided with income-earning developments in the cryptocurrency space, long in the pipeline, that became a reality in 2020. Holders of some smaller cryptocurrencies can already earn income from staking and from transactions fees, and Ethereum 2 joined the ranks in December. Because this staking/fee income is available to any holder, without the need for the computing power needed to produce blocks under the proof-of-work system used in Bitcoin and Ethereum 1, it quite suddenly creates a new incentive for any investor to hold cryptocurrencies. In parallel, decentralised finance (DeFi) transactions, including lending, that allow holders of a wide range of cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin, to earn (further) income, has gone from a theoretical possibility to a reality, albeit initially on a small scale.

The potential is for both staking/fee and DeFi income to grow over time, possibly very rapidly, reflecting rising volumes of real economy transactions, both by retail consumers and in the business to business area, and also financial transactions. The jump in the price of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies when PayPal announced their availability on its platform, albeit with initially restricted transferability, demonstrated investors’ focus on this issue.

The combination of staking/fee and DeFi income allows holders of a cryptocurrency portfolio to potentially earn high single- or low double-digit percentage income. This is highly appealing in a zero-interest world. Especially combined with supply either being strictly limited, as in the case of Bitcoin, or for other cryptocurrencies set by pre-determined rules, which in some cases are linked to transactions volumes (as is proposed for Ethereum). As this yield potential on a limited-supply asset has become apparent to both family offices and institutional investors, it is unsurprising that the universe of cryptocurrency holders has rapidly started to broaden out from the earlier enthusiastic pioneer core, supporting demand.

One way of thinking of this income is that it gives to cryptocurrency holders the profits and wages that accrue to shareholders and employees in a conventional banking system. In this sense, a cryptocurrency is a kind of co-operative, with users both paying to use it (explicitly via fees or implicitly via currency creation), and receiving income from its use. The corollary of this is that cryptocurrencies pose an existential threat to the existing business models of conventional banks and, perhaps to a lesser extent, payments providers. The current world of zero interest rates, compressed credit spreads and flat yield curves adds to this pressure, since banks traditionally made their profits by intermediating credit and through asset-liability maturity mismatch. 2020 saw reports suggesting that, for the first time, a merger between the two biggest Swiss banks might now be a serious possibility. While the outcome of any particular negotiations cannot be predicted, the structural pressure for consolidation, and for focus on client-facing activities that cannot be replaced by decentralised blockchain transactions, suggests that a new wave of mergers could appear in a number of countries before long.

Central Bank Digital Currencies

Another development in 2020 has been the acceleration of activity by central banks in provision of digital currencies. China launched a digital Yuan, initially to a trial group of users, and while other countries have made no commitment, periodic comments have suggested that a topic that was merely the subject of working groups and discussion papers early in the year, may be moving rapidly up to the decision-making boards. Reasons for this could include the rapid spread of cashless transactions during Covid, as well as the desire of the central banks to provide a secure and strong anchor for the rapidly growing technologies centred around cryptocurrencies. Another intriguing possibility is that central bank digital currencies could be used for extraordinary monetary policies previously possible only in economic theory, such as a “helicopter drop” of extra money to all holders, or its opposite, the imposition of negative rates on everyone – though the latter might be seen as confiscatory, and undermine public confidence in the new money.

Many open questions remain about these central bank currencies, notably (i) whether they will be available only to intermediary institutions, direct to the public, or a hybrid that allow public holdings with access via an intermediary; (ii) whether central banks will allow private stablecoins denominated in their local currency (such as DAI for USD or Facebook’s multi-denomination Libra) to circulate in parallel with their official digital currencies; and (iii) what the relationship between the central bank digital currencies and independent cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin might be. The Chinese version may or may not turn out to provide a model followed elsewhere, but for the record, on these three key features: (i) it is a hybrid; (ii) private stablecoins are outlawed; and (iii) the extent of its interaction with the full range of cryptocurrencies is not yet clear, and may well evolve over time.

And, it is the third issue that is most important for the future value of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. There is a possibility that central banks might try to create some kind of total separation. However, this would stymie the development of the technology, since it seems unlikely that the central banks would allow features such as broad DeFi to be developed using their own digital currencies, indeed it is challenging to see how this could be made compatible with the security and control that is clearly needed for an official unit. It therefore seems more likely that the central banks will allow interaction, perhaps limited at first and then broadening, so that the full potential of both decentralised finance and also direct real economy applications such as supply-chain management can be developed using the cryptocurrency units. This scenario would likely be positive for cryptocurrencies, since they would become clear complements to the official digital currencies, allowing the operation on public blockchains of services such as lending, capital issuance, and the tracking of and paying for the online purchases that have boomed during Covid. As such real and financial transaction volumes grew, they would tend to put upward pressure on the prices of cryptocurrencies.

Summary

The Covid crisis has turned out to be a perfect storm for cryptocurrencies. The threat of future inflation from the explosion in government debt remains far beyond the visible horizon, yet it has clearly risen as budget deficits have soared and monetary policy has been eased, and this provides an anchor justification for an increasing pool of investors to hold cryptocurrencies, but especially Bitcoin due to its tightly limited future issuance. More immediately, the intensified monetary easing that has spread the “zero rates” mantra out across the credit and yield curves has coincided with the arrival of income-earning possibilities from staking, fees, loans and DeFi, especially on the new small-cap cryptocurrencies and the emerging Ethereum 2, and the potential for high single or low double-digit earnings is clearly drawing in many new investors. Alongside this, the potential for growth in real-economy transactions, initiated by providers such as Worldline and given prominence by the PayPal move, could be given enormous impetus if the current moves towards central bank digital currencies allow interaction with existing cryptocurrencies, whose operation of digital banking and real economy supply chains would make them the heart of the world’s new digital workshop.